X

Read the article at Kathimerini.gr

September 27, 2025

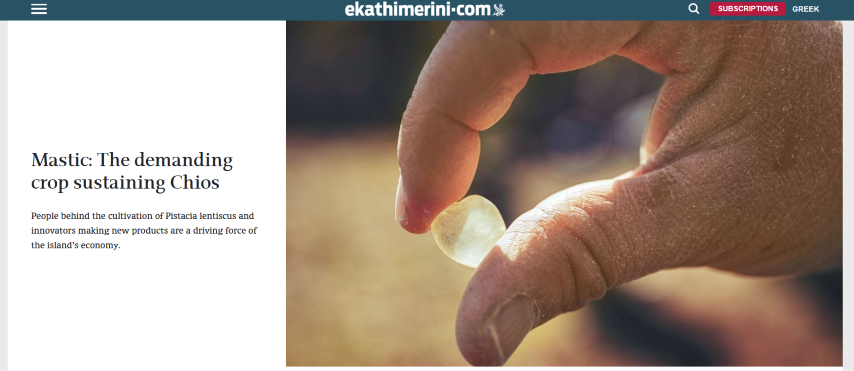

People behind the cultivation of Pistacia lentiscus and innovators making new products are a driving force of the island’s economy

Manina Danou

27.09.2025 • 22:00

Tough, demanding and collective by its very nature, mastic, or mastiha in Greek, is a business that calls for a lot of hands. From tending and scoring the trees, to harvesting the resin and cleaning it, it’s a process that demands patience, precision and care. And people – a lot of people. In the mastic-growing villages of southern Chios, entire families work together to bring in the crop. Young and old, everyone is essential. This is why every root of Pistacia lentiscus is more than a tree; it is part of the family, part of the islanders’ identity. Or at least those in the 24 villages responsible for the island’s output, from Mesta and Pyrgi to Vessa, Tholopotami and Olympoi, to name a few. For these villages, the mastic tree represents roots and a way of life. It has shaped their destiny and even their layout, architecture and demographic.

It is this intrinsic relationship that makes the wildfires that swept across the island this summer, reaching the mastic-growing villages in the south, all the more devastating, as they burned more than 12,000 trees entirely and 8,000 partially. Initial estimates point to losses of around 3 tons for this year, damage that is not just economic but also symbolic. Because the mastic tree – a wild shrub, in fact – is unique to this tiny part of the world. While Pistacia lentiscus can be cultivated in the wider region, it is only in southern Chios that it produces this high-quality, clean resin, for which the eastern Aegean island is renowned. Scientists attribute this uniqueness to a combination of factors: the volcanic subsoil, the region’s distinctive warm and humid microclimate, and the local plant varieties that have evolved through centuries of cultivation.

All hands on deck

We traveled to Chios to meet the people behind the island’s mastiha production: The family of grandfather Dimitris Chrousakis, his son Nikos, and his 8-year-old grandson, who is already growing up among the trees. “He’ll join the business too; none of us gets away,” his father says; Lenia Ziglaki, who founded Mastiha Roots, the evolution of Adopt a Mastic Tree, which today has become a well-rounded initiative connecting people from all over the world with Chios’ mastic trees; Eleni Paidousi, a native who returned to the island as local director of the Chios Mastiha Museum of the Piraeus Bank Group Cultural Foundation when it opened its doors in 2016; the women of the cooperative in Tholopotami, who took over mastiha cultivation from their husbands; and Giorgos Toumbos, president of the Chios Mastiha Growers Association, who supports producers while also leading them confidently toward the future, through Mediterra, the association’s commercial and innovation arm, headed by Giannis Mandalas.

The mastiha business has seen an influx of younger people in the past few years, too, after official recognition of its medicinal properties boosted prices and demand – and made its prospects more attractive to youngsters who had left the island.

“I don’t want you working the trees, little one / Wasting your youth for a drop of resin,” the voice of grandmother Marianthi can be heard singing on an audio recording as we enter the museum. It’s not a hymn to the mastic tree, but a lamentation about a backbreaking job that was once even considered undignified. In Tholopotami – and beyond – most of the villagers emigrated, mainly for America. “We returned as grown women and took over,” says the president of the village’s women’s cooperative, Eleni Fountoukou.

Things have changed since Marinthi’s day and mastiha cultivation is widely respected today. The reorganization of production has played a crucial role in this shift. The Chios Mastiha Growers Association, an essential cooperative founded in 1938, is still the world’s only exporter of this particular commodity. “Do you know of any other producer who knows, with absolute certainty, that they’ll sell their entire output?” comments Eleni Paidousi. The association is obligated to take delivery and sell all the mastic produced by its active members, who come to around 1,700 from among 4,500 registered members. As a whole, Chios produces some 230 tons of mastiha a year, with turnover in 2024 coming to €23 million. Producers rely on the association for every step, from harvest to packaging and the negotiation of prices. More importantly, they rely on it for support and stability.

At the same time, Mediterra has been responsible for reaching out to foreign markets for the past 20 years, but also for designing the Research and Innovation Center, an initiative launched two years ago with the purpose of developing new products made of mastiha.

“When we took on the reorganization of the cooperative in 2022, we had to create something new – free from the hang-ups of the past – that would give us a quick win. That was Mastihashop,” says Giannis Mandalas, referring to the global chain of outlets for Chios’ products. “The idea was new products made of mastiha, which had come to be considered somewhat old-fashioned. There was the ELMA chewing gum with a market share of just 0.5%, and maybe a spoon sweet or a piece of loukoumi. That’s why production had dropped to just 100 tons.”

Today, with more than 200 different products ranging from cosmetics to herbal teas and alternative medicines, Mediterra has succeeded in placing mastiha on the shelves of major concept stores in Japan, South Korea and the United States.

In the field

During our visit in mid-June, there wasn’t much that needed to be done in the groves apart from clearing the ground beneath the trees and sprinkling it with inert calcium carbonate, a process known as “cleaning the table.”

The most important phase starts in early July and involves scoring the trees to release the resin. It is a process known as “embroidering” to produce “tears.”

“All the tools are purpose-built,” says Paidousi. “We call it ‘embroidering’ because the movement is similar to that of the needle. In this instance, human intervention causes production. Basically, we injure the tree so it produces resin to heal itself. If the cut is too deep, the tree will dry out; if it’s too shallow, you won’t get enough resin. The intimacy in the process is why mastic producers love their trees. It is the embodiment of balance between man and nature.”

Once the “tears” of resin appear, they are left to harden on the tree. “You can see them sparkling in the fields, as though the trees have been adorned with crystals,” says Paidousi.

“You need to score the trees early in the morning because the sun softens the resin. You also want to protect yourself from the hard midday sun. But collecting the resin needs to be done at night,” Dimitris Chrousakis and his son Nikos explain.

At best, a single tree can produce around 200-250 grams of mastiha a year. Tholopotami’s cultivators cannot even rely on these small quantities. “Our trees are not as robust as they are further south. Not only do they produce less, but the quality is also inferior, so the rewards are much smaller,” say the women of the local cooperative, who took over the business from their husbands. “You need men to do the heavy lifting, but women are also essential. The clearing of the table has always been our job,” they add.

As many as five to seven incisions can be made on a single mastiha tree, depending on its size. Older trees produce less resin, so they need to be renewed. The Growers Association provides new saplings, though many people propagate them on their own. Still, a mastiha tree lasts a generation, producing resin for about 100 years.

Strengthening the community

Once the resin is collected, it is washed in big cauldrons (some still wash it in seawater) and then cleaned with a small knife, a painstaking and exacting task – usually done by the women – that essentially determines what kind of price the association can ask.

And all this is just a part of the work demanded. “Every mastic tree requires as many as 15 visits by the producer in a season,” says Lenia Ziglaki from the village of Mesa Didima, who took over her father’s trees and launched the Mastiha Roots adoption initiative.

A portion of the contributions sent by sponsors – often foreigners who love Chios and mastiha, and who receive a certificate and photo of their tree, 50 grams of mastiha and updates on each stage of cultivation – returns to the growers and the community through targeted initiatives. In essence, Mastiha Roots is building an international community of producer-supporters.

Nowadays, mastiha cultivation faces two main challenges. The first is climate change, which brings fewer rains in winter, when the trees need them most, and heavier downpours in the summer, which can be disastrous. The second is overcultivation.

“Trees on sloping, semi-mountainous land can’t produce resin every year; they need periods of rest,” says Toumbos of the Growers Association. “But as earnings increased, so did cultivation. The trees became stressed and there were years when, even though more trees were planted, production dropped. For the past two years, we’ve started managing knowledge differently. We run training seminars for young growers, so plant resources are managed in a new way. And our success is that we’ve revived the sector. Today, producers are part of a successful team that can support their families with mastiha. Where once it was thought shameful to be seen tending mastiha trees, now there’s pride in it.”